The Archaeology of 1916 project aims to record what’s left in the contemporary urban landscape of the buildings and sites associated with the 1916 Rising. The task becomes all the more pressing 100 years on as we begin to realise how little is left of Dublin’s early twentieth-century streetscapes and vistas. One site that survived until relatively recently was the Foresters’ Hall, located at the back of 41 Parnell Square (then known as Rutland Square), a structure which itself was only built in 1912. Its history articulates something of the linkages between constitutional nationalism and the more militant tendencies in the run up to the Rebellion and indeed in the years immediately after.

41 Rutland Square as depicted by the Ordnance Survey in 1907 prior to the hall’s construction.

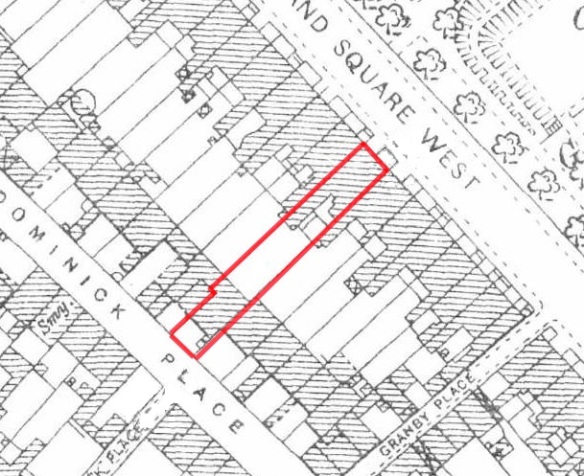

The Forester’s [sic] Hall, Ordnance Survey, 1943.

The organisation was supposedly non-sectarian and non-political, and there was no class distinction within the membership. It can nonetheless be considered an equivalent of the Orange Order, where at its root it was a mutual aid society, established to assist members in financial distress and dependants of deceased members. The membership would partake in public displays at such events as St. Patrick’s Day or on Easter marches, dressed in green regalia with local banners and bands. In later years, the uniform was dispensed with and green sashes, similar to those worn by the Orange Order, were worn instead.

The INF grew rapidly and soon became the largest friendly society in Ireland. It supported Irish nationalism and its constitution called for ‘government for Ireland by the Irish people in accordance with Irish ideas and Irish aspirations’ (Irish Independent, 25 May 1942, 3). By 1914 the order had spread worldwide and had a quarter of a million members in over 1,000 branches. It was particularly strong in Scotland and among the labouring diaspora in Australia and the US. With the establishment of the Free State and the gradual expansion of the social welfare system, the organisation went into decline although some branches still exist in Ulster and north Leinster.

Foresters returning from the funeral of those shot dead by British troops at Bachelors’ Walk, July 1914 (Hulton Getty Picture Collection).

The political circumstances of the popular rejection of Home Rule in Ulster led to the formation of the Ulster Volunteers as an openly armed organisation. This was seen as a useful model by the secret Irish Republican Brotherhood for the establishment of a similar popular body, and a committee began to meet regularly from July 1913 to monitor the situation in Ulster and to encourage the organic formation of a militant separatist force from within a more constitutional milieu. The IRB themselves could not openly take the initiative, where it was likely that any militant organisation would face immediate suppression by the state.

The IRB began the preparations for the open organisation of the Irish Volunteers in January 1913. James Stritch, a prominent member of the Brotherhood, appears to have persuaded the Foresters to build a hall at the back of 41 Parnell Square, which was also the headquarters of the Wolfe Tone Clubs. Anticipating the formal establishment of the Volunteers, classes were held in foot-drill and military movements. These were conducted by Stritch himself together with members of the republican scouting organisation Na Fianna Éireann. They began by drilling a small number of IRB members associated with the Dublin Gaelic Athletic Association, led by Harry Boland. The Volunteer organisation was publicly launched on 25 November, with their first public meeting and enrolment rally at the nearby Rotunda. This brought many more volunteers into the ranks and the Foresters’ Hall became one of the many such halls throughout the city where the organisation trained.

Volunteers undertaking musketry drill, though possibly not in the Foresters’ Hall (AP/RN).

The hall was designed by a notable architect William Alphonsus Scott (1871-1921), who apart from holding the new Chair in Architecture in the National University (succeeding Sir Thomas Drew who had died only two months after his own appointment), had also designed the Town Hall in Enniskillen (1897) and indeed had exhibited a design for the town’s Foresters’ Hall at the RHA in 1906. He was responsible for several ecclesiastical buildings in the dioceses of Kilmore, Raphoe and Clogher and despite a fondness for alcohol in his later years, he was possibly one of the best known architects in the country, with over 120 designs undertaken throughout the island (Larmour 2001).

Tenders for the new hall were invited in March and April 1911, to measure 97 x 30 ft., with a stage, store rooms, lavatories and a small assembly room (Irish Builder 52, 19 March 1910, 181 and 53, 1 April 1911, 210). The successful contractor was John Dillon of Drumcondra, who undertook to build the structure for £1,500 (Freeman’s Journal, 21 March 1911). It would appear to have opened its doors the following year where the nascent Volunteers were drilling there in January 1913.

The construction of the hall after 1912 fulfilled one of the organisation’s objectives to provide venues for Catholic social functions under the general banner of ‘Unity, Nationality and Benevolence’. In this regard, hiring the hall to the Irish Volunteers would have provided an income as much as they supported the organisation’s general principles. Where these were not as ostensibly subversive as those of the more advanced nationalist organisations, it is likely that many activists belonged to both groups.

The Witness Statements in the Bureau of Military History attest to the importance of 41 Rutland Square (prior to the construction of the hall), as the meeting place of the IRB Leinster Council. Recently released files from the National Archives demonstrate that the Dublin Metropolitan Police was well aware of the activities taking place in the hall in the months leading up to the Rising. The hall was placed under surveillance along with a number of key locations, including Thomas Clarke’s shop at 75 Parnell Street, the Irish Volunteers Office at 2 Dawson Street and the headquarters of the Gaelic League at 25 Parnell Square.

Handbill for a benefit concert in the Foresters’ Hall.

The hall seems to have been initially used by Na Fianna Éireann, where the father of a prominent activist Padraig Ó Riain was the caretaker (O’Connell 2012). For many Dublin Volunteers, an inkling of what was about to take place was given at a concert organised by Cumann na mBan on Palm Sunday 1916 (BMH WS0081, Bulmer Hobson) where several secondary accounts of the Rising mistakenly have the hall as the mustering point for Ned Daly’s 1st Battalion on Easter Monday.

The hall continued to have republican associations after the Rising and was used for a period during the War of Independence as a Sinn Féin court, established to supplant the administration of imperial justice imposed by the British:

In the calling of justices, plaintiffs, defendants, witnesses etc. we ran a very great risk of being captured. This was especially so in the case of defendants who were often hostile. However, we did succeed in carrying on and often when calling a sitting of the Court for 41 Parnell Square we transferred same to a few doors down at 46. All classes of offenders were brought before the Courts and dairymen who had put too much water in their milk before delivery to the people were fined substantial sums. The most notable and numerous cases were those in connection with “Process for Civil Bill”. Criminals were often apprehended and taught a salutary lesson. In many cases they were deported. During this period I maintained my membership of ‘A’ Coy 1st Battalion I.R.A., and naturally most of those actively engaged in Court work were members also. (BMH WS0619, Sean M. O’Duffy).

The hall was also the venue for several IRB Council meetings prior to the Civil War, where attempts were made to reach a political accommodation with those who would later take the republican side in the conflict.

The Foresters’ Hall’s associations with militant Republicanism perhaps overshadow its significance as a theatre venue and indeed as a meeting place for the Gaelic League. The first of March 1914 for example saw a production of Seumas O’Kelly’s Matchmakers by the Croke Club, which also undertook a production of Seamus O’Beirne’s An Doctuir (O’Ceallaigh Ritschel 2001, 92-3).

Long after the INF ceased to be a force to be reckoned with, the hall was a venue for ceilidhe and dances. The remains of a secondary suspended ceiling in front of the stage area attest to a modernisation of the venue, possibly undertaken in the 1950s. It’s interesting to contextualise its construction within the trajectory of public usage of the square’s former grand residences in the twentieth century. On Parnell Square (its official name after 1933) the Ierne and National Ballrooms vied with each other seven nights a week well into the 1970s. To these can be added the smaller halls such as the one under discussion, the Irish Club and indeed the Teachers’ Club (which still survives several doors up from No. 41).

The hall appears to have been derelict for at least fifteen years and was surveyed by the project prior to the removal of its exposed roof trusses which were endangering the party wall to a crèche in the adjoining property. It remains roofless, within the curtilage of a Protected Structure in private ownership.

The Foresters’ Hall from 41 Parnell Square.

Interior of the Foresters’ Hall prior to the removal of its roof structure.

Detail of roof structure.

The stage.

Larmour, P. 2001. ‘‘The Drunken Man of Genius’: William A. Scott (1871-1921)’. In Irish Architectural Review, 3, 28-41.

O’Ceallaigh Ritschel, N. 2001. Productions of the Irish Theatre Movement, 1899-1916: A Checklist. Dublin.

Not just the Leinster Council. The main building appears to have been the habitual meeting-place of most Circles in the city, and to have been host to other events such as the building first held in Easter Week by the ‘Special Unit’ (including MacBride) in Easter Monday.

Regrettably, sometimes it’s unclear whether or not this concert hall or the townhouse in front were being referred to – although sometimes you do get people specifying which, right down to the meeting room no. I get the impression that at least part of the function of this building was as a property investment vehicle, just like the Irish Life Building.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Possibly! I think the idea that a few circles met there is good. They’d be in the smaller spaces in the primary structure to the square. The was wasn’t built until 1912 and we can’t find a reference to an opening date. The ‘Special Unit’ I know little enough about, but it has the makings of an interesting novel …

LikeLike

You’re welcome. My interest in Ceannt, Kettle and MacBride comes from research I’ve been doing for DCC’s upcoming book on the Easter Rising into past Dublin Corporation employees who were involved in the Rising.

If you drop me an email, I’ll send the full document on. The ‘Special Unit’ has been one of the big surprises.

LikeLike

The Wolfe Tone Memorial Committee (the public cover of the I.R.B. Supreme Council) typically had its meetings at No. 41 – those which weren’t held at the Clontarf Town Hall, at least. It seems to have convened as the WTMC, conducted its’ business, and re-convened in the same meeting. A number of Volunteer units were also based out of this building, and it was occupied and held on the first day of the Rising by J.R. Reynolds’ ‘Special Unit’.

Incidentally, that range photograph likely can’t be the Foresters’ Hall, because it contains both Larry Kettle and a poster for the National Volunteers. It’s possibly the basement of No. 44 (the A.O.H. Hall and an NV building until the NV split in 1917), or else the Banba Rifle Club (in Harold’s Cross, I believe) in which Kettle was involved.

LikeLike

We’ve been looking for the Banba Rifle Club. It sounds like a band doesn’t it?

LikeLike

‘An interesting recollection I have is the question of practice for the men in shooting from a rifle, to learn to aim, etc., and a scheme was brought about – I am not sure by whom, but the three men concerned in it were Commandant Ceannt, Larry Kettle, and the Manager of the Greenmount Oil Company, whose name I forget, to make use of the Rifle Club which met at the Greenmount Oil Works, where a miniature rifle range had been erected. By some means some old .22 bore Martini rifles had been secured and those of us who possessed these would meet every Sunday and practice shooting at the target at the Greenmount Oil Works.’

I’ve no idea where ‘Greenmount Oil Works’ was, but Ceannt and Kettle were both involved in the Banba Rifle Club (as was Cathal Brugha).

LikeLiked by 1 person

That’s great thanks! The Greenmount Oil Works were/are still just off the canal to the west of HX Road. Never knew it was the family business of Loius le Brocquy!

LikeLike

(That last was from BMH WS1756, Seumas Murphy.)

LikeLike