Northumberland Road is today a quiet, leafy, residential street leading to a bridge over the Grand Canal, over which there is a direct route into the centre of the city. For a couple of days over Easter Week 1916, this street lined with terraced houses and its immediate environs saw some of the bloodiest fighting of the Rebellion.

A photograph of No 25 Northumberland Road, in the immediate aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rebellion.

During the 1916 Easter Rebellion, it was in this peaceful suburb on Dublin’s south side, that a small group of Irish Volunteers inflicted significant losses on the Sherwood Foresters who were attempting to advance into the city. Fatefully for the British soldiers in the ensuing battle, the Irish Volunteers had occupied two superbly located sites: an end of terrace residence at No. 25 Northumberland Road and Clanwilliam House across the canal. Two less strategically located buildings, the Mission Hall and St. Stephen’s Schoolhouse were also occupied, as well as a builders’ yard to the east of the bridge closer to Company HQ at Boland’s Bakery. The story of the fighting along Northumberland Road itself and the ensuing battle of Mount Street bridge is perhaps one of the most familiar of the 1916 Rebellion (and a subject of many fine studies, in particular, see the Contested Memories: The Battle of Mount Street website here), and will be quickly summarized below. What is less well-known is the story of the destruction to property, the aftermath of the battle, and the ways that the residents of the street repaired the damage, and ultimately the physical remains that can be seen today.

In this blog post, we reflect firstly on the action at, and damage to, No. 25 Northumberland Road, and then the efforts made to repair it by its owner, Michael Cussen, in the weeks and months afterwards. Tracking the process of repairing the damage and the claims and decisions made are key to understanding what archaeological traces survive today from the Easter Rebellion at No. 25 Northumberland Road.

But, it is also a story about how a building in a middle class suburb was wrecked, and how its presumably prosperous owner used his resources, solicitors, architects and builders, to seek redress through the authorities and repair his property. In some senses then, it is a very different story to the impact and experience of the Rising in the working-class districts of the city, as described previously in this blog, and most recently here.

Aerial view of the crossroads at Northumberland Road/Haddington Road. The No 25 Northumberland Road building is at the lower centre; Haddington Street church is the grey building off to the extreme left. Northumberland Road itself extends off from lower left to upper right, up to the Grand Canal, across which is the location of the original Clanwilliam House, occupied today by the brown building at extreme upper right. (Image: Google Earth).

No. 25 Northumberland Road is today a large, handsome, three-story Victorian terraced building, located at the corner of Haddington Road. This broad crossroads has excellent views in several directions, most notably to the southeast along the road leading into the city from Kingstown.

No 25 Northumberland Road today. In the main part of the fighting, Lieutenant Malone was firing from the bathroom of the “third floor”, to the side, while Grace was shooting from the “second floor” overlooking the street (Photo: Aidan O’Sullivan).

The story begins

The story of the building’s role in the battle begins on Easter Monday, 24th April 1916, when James Grace, Paddy Rowe and Michael Byrne, of C Company, 3rd Battalion Dublin Brigade of the Irish Volunteers, were sent by Lieut. Michael Malone from Mount Street Bridge to the junction of Northumberland Road and Haddington Road, with the instruction to ‘cover the gates of Beggars Bush Barracks’ (James Grace, BMH WS310).

After a tense encounter there with two local men, they were joined on Haddington Road, by Michael Malone, who then told his men to occupy 25 Northumberland Road. Grace in his witness statement described how ‘I smashed in the yale lock with the butt of my rifle and we immediately prepared the house for a state of siege, putting up barricades, filling vessels with water and so on’. The destruction had begun.

When compiling his witness statement in October 1949, James Grace states that the house was by that time in flats but that otherwise it was ‘practically the same now as it was then, except that there is now a front entrance to the basement’ (a telling detail, given the difficulty the British troops had in attacking the house in 1916). It is clear that the house itself—in 1916 an owner-occupied residence—was empty at the time of the volunteers arrival. James Grace claims in his statement that the owner and resident, Michael Cussen, was supportive of the Volunteers, stating that ‘the Cussens who owned the house were also friendly, and having been told of events to come had sent the servants away and evacuated the house themselves’ (WS 310). In contrast, Cussen himself, in a subsequent letter written to the Under Secretary Sir Robert Chalmers, claimed that ‘I need scarcely say that I have had no connection whatever with the rebels, and had no previous knowledge of their designs’.

But, of course, he would have said that.

Michael Cussen was a retired Customs and Excise Officer. He was registered in the Dublin City Electoral Rolls for 1914 as resident at 29 Northumberland Road (the resident of 25 was struck off the list, and presumably Cussen purchased the property thereafter).

The fighting starts

The fighting at No. 25 Northumberland Road began on the afternoon of Easter Monday, when a Company of G.Rs. – a form of local home guard – approached from the direction of Ballsbridge. The volunteers ensconced in No. 25, ‘opened fire on them and they scattered and retreated’ (BMH WS310). Although they carried arms, these were reputedly unloaded and the G.R.s retreated to Beggars Bush barracks, located just around the corner.

Through Easter Monday 24th April, and Tuesday 25th April, the Volunteers inside the house had to cope with persistent sniping ‘in particular from a house right opposite giving us a lot of trouble’. Lieut. Malone and Grace proceeded to the top of the house; Grace was asked by Malone to go to the right-hand room, to draw the snipers’ fire, and he was able to then identify that the location of the sniper was ‘… in the right-hand top window of the house opposite which was No. 28’. Malone fired a few times, and the ‘sniper crashed down, dragging with him the window blind’ (BMH WS 310, page 7).

About 2.30am, before dawn of Wednesday 26th April, Malone sent the two boys, Paddy Rowe and Michael Byrne, away on dispatch duty; in reality to get them away from impending danger. Grace prepared the building for battle setting ‘booby traps in the hall and on the stairs’ (BMH WS 310, page 8).

About noon of that day, Wednesday, they were told by Grace’s sister and Miss May Cullen that British soldiers had landed at Kingstown and were advancing on the city. The 2/7th and 2/8th Battalions of Sherwood Foresters, mostly young, inexperienced and barely trained soldiers from Nottingham and Derbyshire, were marching towards Northumberland Road. A building, Carrisbrooke House, previously occupied by the volunteers further south along the road had now been abandoned, placing No. 25 Northumberland Road to the front of the Volunteers’ positions.

Sometime after noon Malone ‘went into the bathroom, the windows of which was on the side of the house looking towards Ballsbridge’, and spotted ‘khaki clad figures advancing’. Malone opened fire from this bathroom window, ‘which was on the third floor’. As Grace states ‘it was from this window that Micheál operated practically all the time – Malone’s window I still call it. I followed suit from another window on the second floor’ (BMH WS 310).

There were casualties immediately among the bewildered British troops, with one secondary account claiming that at least ten were killed in the first volley of shots as they were being fired on from both 25 Northumberland Road and Clanwilliam House across the canal. According to Grace, the British soldiers took control of ‘almost every house within point blank range’, and put up a terrific fire on the windows of the house, forcing Grace to move continually and take cover often.

They attempted bombing attacks at 5 o’clock and about 8.30, whereupon Grace took up position downstairs on the hall floor. Hearing movements in the ‘room on the left’, he fired through the panels and heard a rush of feet away from it. A few minutes afterwards, he heard the ‘crashing of glass and a door at the rear with steps leading into the back garden was burst open and some English troops rushed in’. After he emptied a fresh rifle clip at them, they retreated for a moment, before making a fresh rush and Grace ‘was driven down the stairs to the kitchen’ in the basement (BMH WS 310, page 10).

At this point, Grace heard Malone rushing down the stairs to his aid, calling out ‘alright Seumas, I’m coming’. Grace himself knelt at the door of the kitchen firing up at British troops that had appeared at the head of the stairs. From there he heard the crash of the volley and the shouts of the troops as Michael Malone was killed.

Emboldened by ‘desperate courage’, Grace rushed to the ‘small cellar window’ at the front of the house, and fired upon an ‘officer leading some men up the steps to the front door’, causing him to drop down the steps. His automatic was now jamming from the heat of firing, and he tried to cool it under the water tap in the scullery, after which he fired through ‘the chinks in the shutters of the kitchen window, whenever he saw an English soldier’.

James Grace continues his witness statement as this particular battle drew to an end.

‘Just then a bomb was thrown down and exploded at the kitchen door to my right. There was also a bomb hurled through the little window of the cellar from which I had been firing. I took cover behind a gas stove and after that had some room to room, firing at the English troops in the basement. The automatic still kept jamming now and again.

We had originally arranged to make a final stand at the top of the house, having left upstairs, loaded rifles with bayonets fixed, one Lee Enfield and two Howth mauser rifles, but the forcing of the glass-panelled door at the end of the rere hall corridor by the enemy separated Micheál and myself and ruined our plans.

About 10 o’clock that night a whistle below and I heard a voice shout out, “clear the streets for a bayonet charge”. I now got desperate and rushing to the basement corridor I flung aside the heavy iron garden seat which barricaded the rere kitchen door and shot back the bolts. Just as I was getting through the door I was fired on from the stairway and on returning the fire shot my way out through the back and escaped over the garden wall into Percy Lane, but I realized I was trapped within the enemy lines‘ (James Grace, BMH WS310, page 10-11).

James Grace was later captured on Saturday in a shed at the rear of 60 Haddington Road. His witness statement contains the rest of his story and the things he saw, including English troops holding Mount Street Bridge, and Clanwilliam House in flames, but the fight for the building at 25 Northumberland Road itself was over, with English soldiers dead and wounded on the streets, and the body of Lieutenant Micheál Malone within.

The battle over, and the damage starts to be assessed

If the battle was over, then Michael Cussen’s problems had just begun. There are several Property Losses (Ireland) Committee files (which can be downloaded here: PLIC_1_116; PLIC_1_2306; PLIC_1_4351) that record what Cussen and his solicitors had to do next.

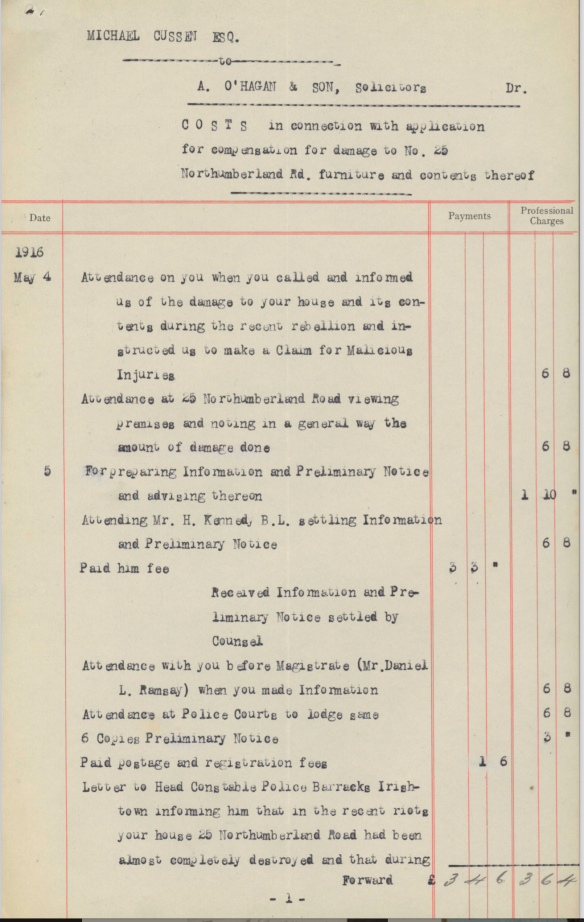

His first task was to assess the damage to his property. It seems from his own statements that the military occupied his house for about 10 days after, and he only entered his house for the first time on 4th May 1916, probably with his solicitor from Arthur O’Hagan & Son, who later lists such a visit amongst his fees (PLIC_1_4351).

First page of Michael Cussen’s solicitor’s listing of payments made and fees incurred, indicating the initial visit on 4th May 1916, and correspondance, as part of the review of damage; PLIC 1 4351 file).

He would have immediately seen that he now had to contend with a wrecked house, destroyed or damaged furniture and lost possessions, and was also facing into the uncertain legal process of seeking compensation from the local authorities, his own insurance companies and/or from the British government. By implication, in a phrase used in one of his letters dated to 1st July, he also had to worry about the further looting of the existing building, which still stood empty—presumably the army had left, and the building could now be entered by others. It is clear that things were stolen, but by whom is never clear (was it the soldiers, or opportunistic locals, or others from further afield?)

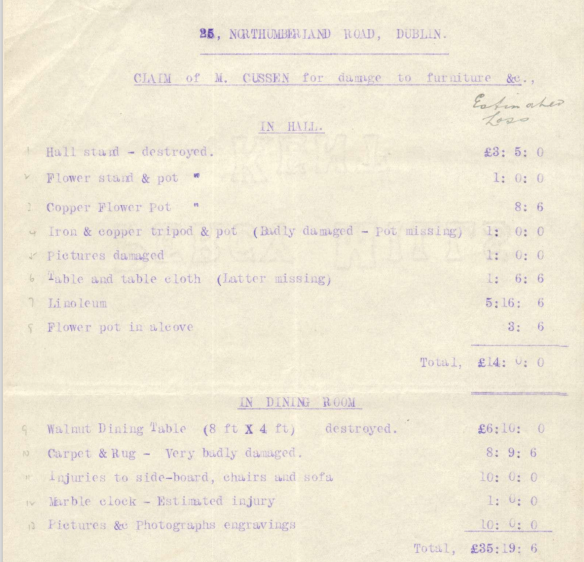

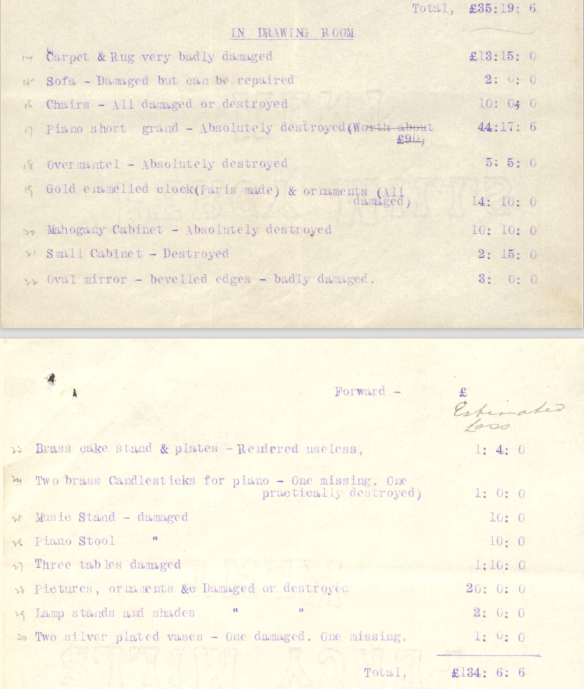

The sheer scale of the damage to 25 Northumberland Road can be seen in a document in PLIC_1_116, entitled ’25, Northumberland Road, Dublin, CLAIM of M. Cussen for damage to furniture &c.’. This document, probably prepared in early June 2016 as part of a claim to PLIC, systematically describes and lists estimated losses at 25 Northumberland Road (PLIC_1_116). The losses were clearly extensive and are ordered in the document by room, including in order of listing: damage in the hall; dining room; drawing room; sitting room (study), principal bedroom; daughter’s bedroom; workroom; dress room; stairs; general; blinds & curtains; glass and china; cutlery etc.; beds and bedding; poles for curtains; as well as a claim by Mrs Cussen, for clothes and jewellery. It is difficult to be clear which rooms listed by Michael Cussen correspond with those described by James Grace in his Witness Statement, but there are some obvious links.

Damage listed in the hall and dining room of No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116).

In the hall (where at one point during the fighting, James Grace lay on the floor), the items destroyed included a hall stand, a flower stand and pot, copper pots, pictures, a table and table cloth (latter missing), as well as lineoleum. The list next mentions the Dining Room – possibly off the hallway, and at the front of the house – where a walnut dining table was destroyed, and a carpet and rug, side-board, chairs and sofa damaged.

Damage listed to the ‘Drawing Room’ of No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116).

In the drawing room, which would most likely have been behind the Dining Room, we read of a carpet and rug ‘very badly damaged’, a sofa which was damaged but can be repaired’, whereas a ‘piano short grand’ was absolutely destroyed and ultimately valued at £44.17.6. In the sitting room (study), a book-case was destroyed, and books were damaged and rendered useless, as well as a safe which was destroyed and rendered useless, though there was also a cost listed for opening it.

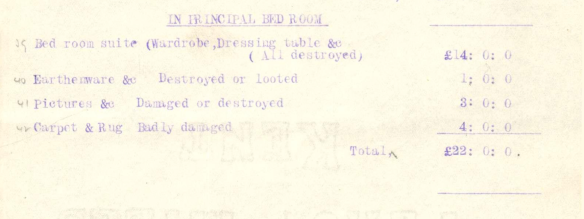

Damage listed to the ‘Principal Bed Room’ at No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116)

If as seems likely, the bedrooms were upstairs, then the principal bedroom’s wardrobe, and dressing table were all destroyed, earthenware was destroyed or looted, and pictures, carpets and rugs were also “badly damaged”.

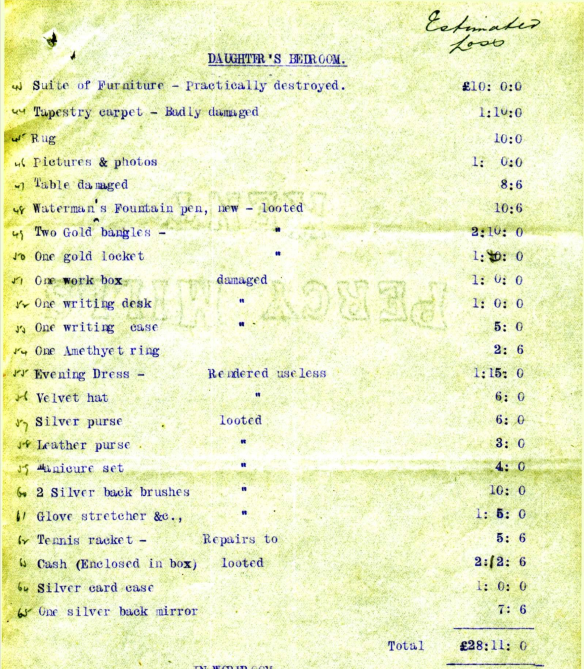

Damage listed to ‘Daughter’s Bedroom’ at No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116)

The daughter’s bedroom also has suite of furniture ‘practically destroyed’, and a long list of personal possessions looted (including a ‘Waterman’s Fountain pen, new – looted’, as well as two gold bangles), or damaged. An evening dress was rendered useless.

In the dressing room, Cussen’s own clothes including five pairs trousers, 3 vests, a dress suit, hats, an overcoat, brushes, combs, handkerchiefs, a hat case, socks, were all damaged, destroyed or looted.

Damage listed to ‘Dressing Room’ at No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source: PLIC_1_116).

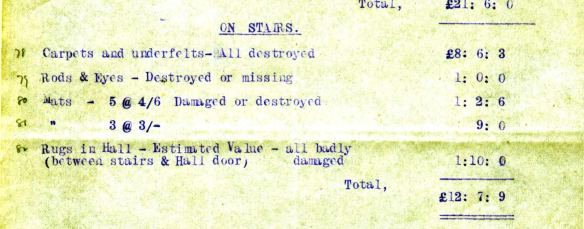

The stairs, where Lieutenant Michael Malone most likely met his death, had its ‘carpets and underfelts-All destroyed’.

Other losses in the house included wines, spirits, tea, sugar, cutlery, while beds and bedding needed to be cleaned or replaced.

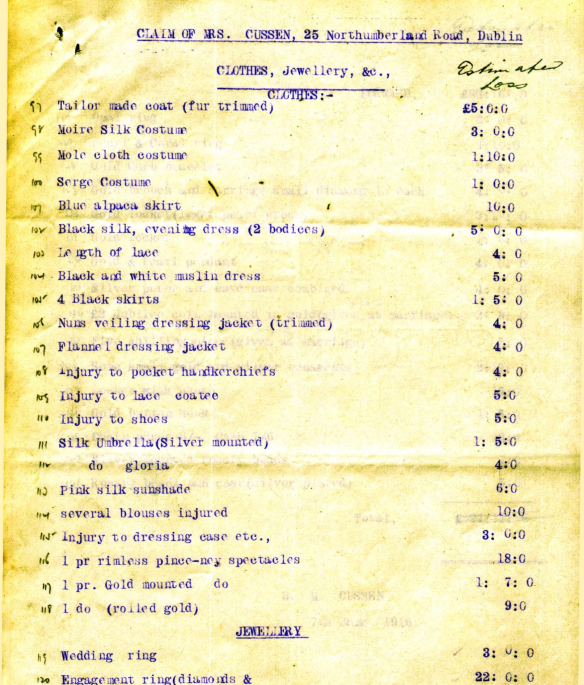

Mrs Cussen’s claim for clothes and jewellery lost is also extensive, with 22 listed items of clothing (some of them multiple) and 23 items of jewellery. Amongst the latter were her wedding ring, engagement ring, diamond and sapphire earrings, a pearl necklet, a ‘2 Jubilee coin mounted in gold (given at marriage)’, a ‘Five shilling piece (given at marriage)’, as well as rosary beads. Most likely these were looted or stolen from the house by the soldiers, or by someone else when the house was unoccupied. A summary of annexed claims puts the total losses of property and costs of removal and storage of furniture at Strahan and Co. at a total of £539.9.9.

Claim for loss and destruction of clothes and jewellery at No. 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116)

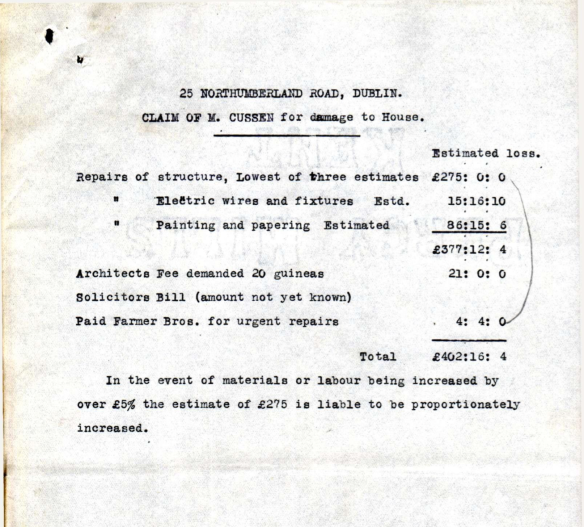

A separate claim for damage to the house ’25 Northumberland Road, Dublin, Claim of M. Cussen for damage to House’ (PLIC_1_116) lists repairs of structure (lowest of three estimates) at £275.0.0, of electric wires and fixtures £15.16.10, and painting and papering at £86.15.6, which had to be combined with an architect’s fee of 20 guineas, a solicitors bill, cost then unknown, and a payment to Farmer Bros. for urgent repairs £4.4.0 (presumably for doors to secure the house?). The total estimated loss for the house was £402.16.4.

‘Claim of M. Cussen for damage to House’ at No 25 Northumberland Road (Source PLIC_1_116)

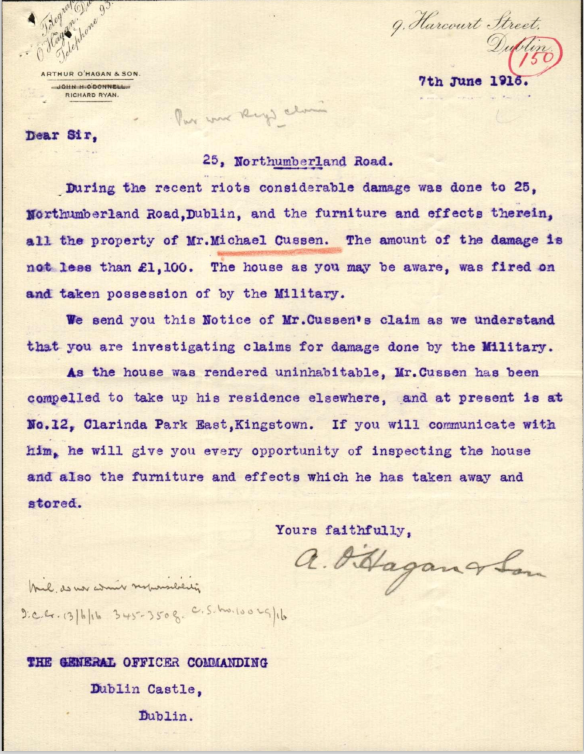

On the 7th June 1916, Cussen’s solicitor Arthur O’Hagan sends a letter to the General Officer Commanding, Dublin Castle, making a claim for compensation (PLIC_1_116).

The letter sent by Arthur O’Hagan on 7th June 1916, to the General Officer Commanding, making a claim for compensation (Source: PLIC_1_116).

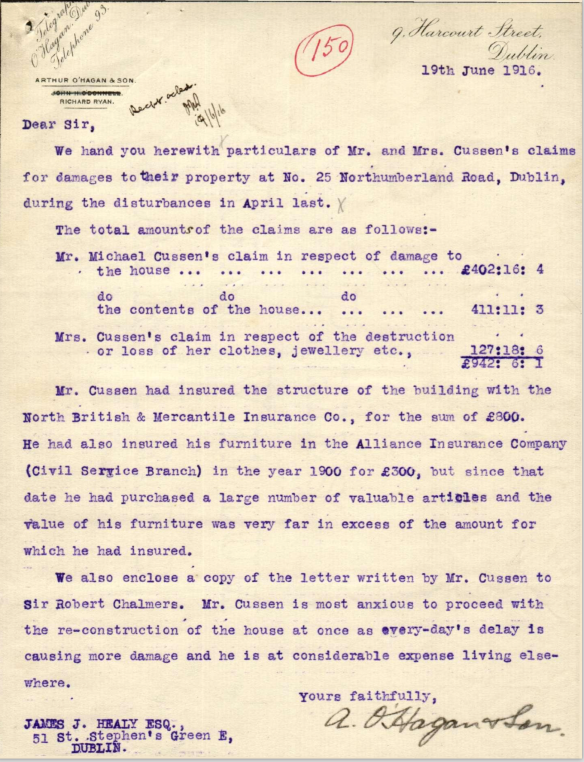

We also have a letter written on 19th June 1916, from Cussen’s solicitor to James J. Healy Esq., 51 St Stephen’s Green E, outlining the particulars of the claims for damages to their property at No. 25 Northumberland Road, amounting to £402.16.4 for the house, £411.11.3 for the contents and £127.18.6 for Mrs Cussen’s claim in respect of the ‘destruction or loss of her clothes, jewellery etc.’.

The letter by Michael Cussen’s solicitor, of 19th June 1916 (Source: PLIC_1_116).

A solicitor’s letter affirming that Mrs Cussen’s loss of jewellery and clothing amounted to £127.18.6 was also submitted to the General Officer Commanding on 16th June 1916 (PLIC_1_2306 ).

Michael Cussen had insured the structure of the building with the North British & Mercantile Insurance Co., for the sum of 800. He had also insured his furniture in the Alliance Insurance Company (Civil Service Branch, [he being a retired C&E officer]) in the year 1900 for £300, but since that date he had purchased a large number of valuable articles and the value of his furniture was very far in excess of the amount for which he had insured. A later note on this by his solicitor’s states that Cussen’s insurance company had denied liability (PLIC_1_4351). Enclosing a copy of the letter sent to Sir Robert Chambers, Cussen’s solicitor also states that Mr Cussen ‘is most anxious to proceed with the reconstruction of the house at once as every-day’s delay is causing more damage and he is at considerable expense living elsewhere’ (PLIC_1_116).

Cussen’s handwritten letter sent from Clarinda Park, Kingstown (another prosperous square, in today’s Dun Laoghaire) to Robert Chambers gives us a strong sense of his sense of shock of the destruction of the property, and is worth reading in full (PLIC_1_116).

“12 Clarinda Park, East,

Kingstown,

13th June, 1916

Sir,

In the recent rebellion the rebels in my absence took forcible possession of my house at 25 Northumberland Rd, Dublin. It remained in their possession until, after a few days fighting it was taken from them by the military, who then entered it and remained in occupation for about 10 days. In the fighting that took place the house was practically wrecked, and when I entered it on 4th May, the earliest date on which it was practicable for me to do so, I found the doors, windows, floors, ceilings, roof, etc. broken, the walls badly injured, and almost all my furniture etc. wholly or partly destroyed. I also found that my wifes jewellery and other valuable articles had been taken away. The losses sustained by Mrs Cussen and myself are very considerable amounting in the aggregate as I now find to over £900, and we propose to submit claims for compensation for them to the Committee appointed by the Government to enquire into such losses. We have already made claims against the County and the City of Dublin, but the cases have not yet been dealt with.

I desire to commence repairing my house as soon as possible. I have engaged the services of an Architect who has obtained the necessary estimates, and I am ready to commence the work, but I am advised not to do so pending the inspection of the premises by an official appraiser or inspr. It is most desirable that the commencement of the work should not be deferred, as owing to (the injuries to the) roof and waterpipes, every day’s delay causes further damage Besides, myself and family are living in hired appartments at considerable expense.

Under the circumstances mentioned I should deem it a favour if you would be good enough to bring my case under the immediate notice of the Committee referred to and urge them to depute an appraiser or other officer to examine my house at Northumberland Rd. The key is kept at (No 30 Northumberland Road, Dublin).

I am a retired Collector of C. & E. and prior to my retirement about 5 years ago was stationed at Belfast. I retired under the regulations having completed 40 years service, and am in receipt of the maximum pension that (was) payable to me. I need scarcely say that I have had no connection with the rebels, and had no previous knowledge of their designs.

I should be greatly obliged if you would favour me with an early reply.

I am etc.

M.Cussen.”

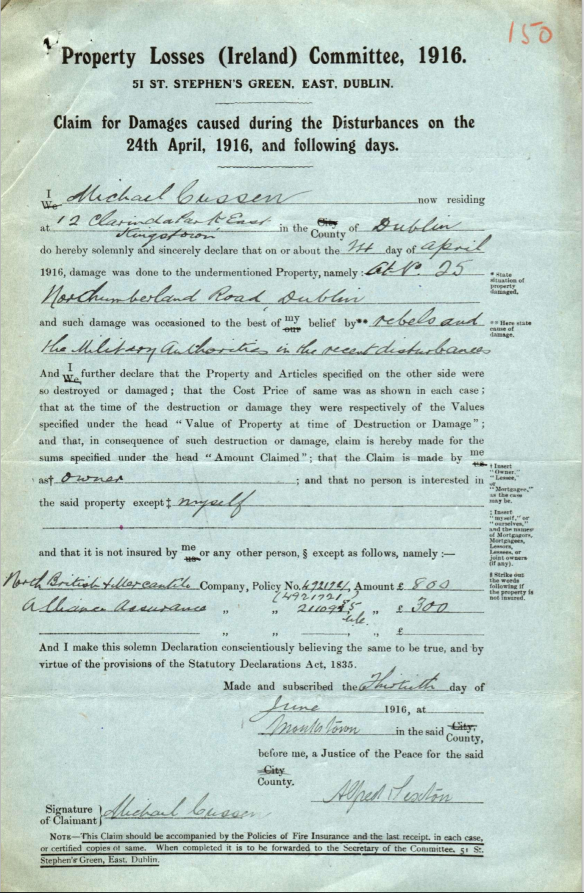

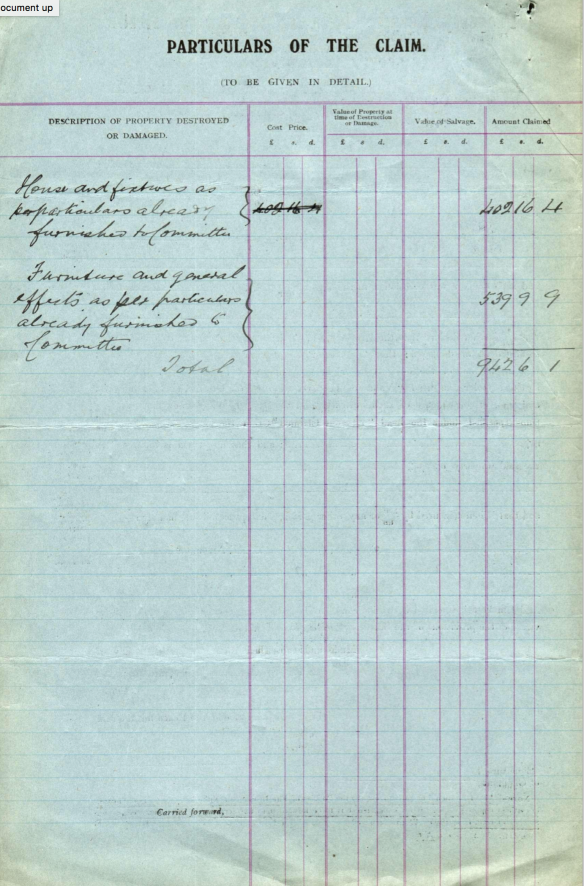

Cussen filled out his formal claim to the PLIC on 30th June, 2016, on the Property Losses (Ireland) Committee, 1916 blue form, listing his claim at “House and fixtures as particulars already furnished to Committee at a total of £402:16 shillings and 4 pence, with an added claim for ‘Furniture and general effects as per particulars already furnished to committee” of £539:9:9, amounting to a total claim of £942, 6 shillings, 1 pence. These figures equate to those listed in detail above.

Michael Cussen’s formal claim on 30th June 1916 to the Property Losses (Ireland) Committee.

On 1st July 1916, Michael Cussen wrote to the Secretary of the Property Losses Committee outlining the basis for his claims, and presumably submitted his full PLIC claim form at that time. Rather than edit it down, or paraphrase it, it is simpler and clearer to offer it in full here (PLIC_1_116).

“12 Clarinda Park, East,

Kingstown,

1st July, 1916

Sir,

I beg to send you herewith my claim for compensation made out on the proper printed form. I have ordered in it the amounts in brief, as suggested to me by Mr Walter Hume, the full particulars being supplied in my original claim. I have handed the two policies of Fire Insurance to Mr Hume’s representative at his office, and I enclose the last receipt from the North British & Mercantile Company. I have not been able to find the Alliance receipt but I have applied for a certified copy, and shall forward it in due course.

I should like to submit the following observations, under the respective headings for the consideration of the committee:-

(1) Insurance on furniture etc.

The amount of this policy is only £300. This amount was sufficient at the time the insurance was effected, but since then I have purchased large quantities of furniture. tc but neglected to insure for a larger amount. There can, however, be no doubt as to the extent of my losses, and the claim should be allowed in full.

(2) Removal of furniture etc

Owing to the state of my house and to prevent further looting, it was necessary to remove my furniture and affects to a secure place and accordingly I had them removed to Messrs Strahan and Co stores, where they remain. Had this not been done, my losses would have been far greater, and the amount of my claim would be much more than it is.

(3) Architect’s Fee.

It was necessary for me to employ an architect. I could not myself prepare specifications nor see that the proper materials were used and the work properly performed. The fee demanded appears to be reasonable.

(4) Law expenses

I have made a claim against the local authorities, but it has not been dealt with by the Recorder(?). A solicitor and counsel have been emplpoyed and expenses necessarily incurred. I do not yet know the amount of the latter, but as soon as I receive the bill of costs, I shall forward it to you the Committee.

(5) Rent of apartments.

I have been paying rent for apartments at my present address since the 25th April last and this expense will be continued until my house is ready for occupation. I have made no claim in respect of rent, but if the government should modify its attitude as regards consequential damage, I shall submit a claim for it.

I have arranged to hand over to Mr Hume on Tuesday next the tenders received for repairing the house, &c together with the stamped deed of agreement between me and Messers Bolger & Doyle builders. In this agreement the dates of payment are specified. I expect the whole work will be finished by the end of September, and it is desirable that whatever amount of money I may be considered entitled to receive should be paid to me before then.

I am, Sir,

Your obedient servant,

M. Cussen

The last letter from Michael Cussen is written on 31st July 2016 (PLIC_1_4351). This is a follow up letter, explaining that he had previously mentioned his ‘law expenses’ but had not included them, as they were unknown to him at that time. He goes on

In my claim for compensation for damages in connection with my house at above address, I referred to the law expenses incurred by me, but did not state the amount under this head as it was not known to me when making out the claim. I am now in receipt of my solicitors’ bill of costs, which I enclose herewith, and I request that you will submit it to the Property Losses (Ireland) Committee and ask them to be good enough to forward it to H.M. Treasury to be considered with my claim and as forming part of it.

Before the Government had declared its intention of making a grant to cover losses caused by the revolt I had commenced an action against the local authorities to recover my losses but at the instance of the Irish Attorney General, as I understand, my case and all similar cases have been struck out by the recorder of Dublin, who would have dealt with them in the ordinary course, and there is now a Bill before Parliament (Civil Courts Procedure) which provides that no claim of the kind referred to above shall lie against the local authority for losses sustained during the rebellion.

Under these circumstances, I respectfully submit that the law costs incurred by me in this case should be allowed.

I am,

Sir,

Your obedient Servant,

M. Cussen

A small note to the bottom left of the first page notes ‘Telephone Messers Hume who dealt with Cussen’s claim. They would not admit any claim for law costs’. Initialed 9/8/2016, it would appear Cussen was unsuccessful in that particular aspect.

The Solicitor’s Costs (PLIC_1_4351) themselves make very interesting reading. The list of payments and costs lists visits to 25 Northumberland Road itself, to the engagement of counsel, to attendance at a Magistrate and Police Courts, and to the writing of various letters, including the engagement of an architect, Mr Sheridan. It is obvious that solicitors and civil servants were kept busy in the weeks and months after the 1916 Easter Rebellion.

Finally, a fateful and poignant note is also to be found in the solicitor’s list of fees, stating that “during the period of disturbances and riots the body of a man was buried in the garden near the conservatory” and requesting of the Head Constable Police Barracks Irishtown to take “the neccessary steps to have the body removed”. Similar letters were sent to the General Officer Commanding, and to Mr Joshua C. Manly, Executive Sanitary Officer Pembroke Urban District; the body was removed before 13th May 2016, according to a later note in the solicitors’ fees.

Michael Cussen’s solicitors costs of payments and fees, mentioning a letter sent to Head Constable Police Barracks Irishtown requesting that a body buried in the garden be “removed” (Source: PLIC_1_4351).

This was the body of Volunteer, Lieutenant Michael Malone, who was killed inside the house and had presumably been hastily buried in the back garden by British soldiers. As James Grace’s Witness Statement informs us (BMH WS 3010), his body was later removed to Glasnevin cemetery where upon it being re-opened for identification, James Grace had a

‘last glimpse of my leader and comrade in his blood-stained olive green uniform. Micheál and Seán Cullen of Boland’s Garrison and myself fired three volleys over his grave in salute of one of Ireland’s most faithful sons – a loyal comrade, a gallant leader, a brave and fearless soldier. Ar dheis Dé go raibh a anam’.

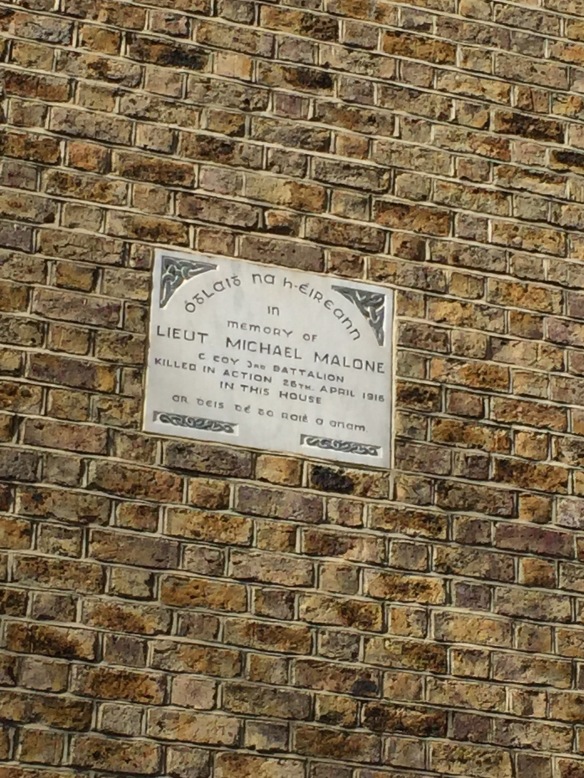

The monument to Lieut. Michael Malone C Company, 3rd Battalion, “killed in action”..”in this house” on the modern facade of No. 25 Northumberland Road. (Photo: Aidan O’Sullivan).

25 Northumberland Road today

So, what is Northumberland Road like today, or more specifically, can we see traces on the street of the events of 1916?

Lieutenant Michael Malone is prominently commemorated in a plaque on the front wall, looking out into the street. The building itself was also photographed after 1916 (see image at the top of this post), and although taken from a distance, it appears to show broken windows, particularly the two side windows of the hall looking out over Haddington Road, where there is also a suggestion of damage to the bricks. The small window at the back, on the third floor level, would seem to be the bathroom window where Malone was stationed and again the window glass is smashed. The front of the house is in shadow in the photograph, where James Grace was shooting from, so nothing at all can be made out there. Otherwise, the quality of the photograph is too poor to make much more else out.

We don’t know, as yet, how much repair was done externally to 25 Northumberland Road. On balance, given the scale and meticulousness of the financial claims submitted, and the engagement of an architect Mr Sheridan, we would have to conclude that Michael Cussen would have hardly left badly damaged brick in place, or the walls unplastered or repaired where it was possible to repair it. The bricks could have been chased out and the side wall of the house replastered.

A view of the south side of No. 25 Northumberland Road today. The very small windows are more recent insertions. We assume—we could be wrong—that the bathroom that Lieut Malone was shooting from was either located at the window over the porch, or at the windows off to the extreme left (Photo: Aidan O’Sullivan).

Having said that, there are both possible traces and probable traces of bullet strikes at the corner of the building.

General view of holes and infilled repair on plaster of side wall, which may of course long-postdate the 1916 Rising, and importantly a possible bullet strike high up, on the granite quoin, five blocks from the roof, at the upper right corner of this photograph (Aidan O’Sullivan).

Firstly, there are some various general marks and imperfections on the plaster over the main side window on the gable end (see below). In the contemporary photograph, there is ivy in this location, and hints of damage there. The marks visible today may not be significant, they could be very recent repair, or they could be repair over bullet marks if the original wall was not wholly plastered or the underlying wall was weakened here.

However there are also some probable bullet strikes on the granite quoins. It is impossible to prove that these are the result of the 1916 fighting, but these marks are certainly very like other definite bullet strikes that can be seen elsewhere in granite around Dublin City centre; most notably at the Fusiliers’ Arch on the corner of St. Stephen’s Green; on the granite façade and window surrounds of the Royal College of Surgeons, overlooking St Stephen’s Green; and furthermore on the granite facades of the Four Courts building on the River Liffey, where there is definite battle damage from 1916 and the fighting at the start of 1922 Civil War.

On balance then, the 25 Northumberland Road marks compare very closely with bullet marks on those granite facades. We can take it as a probability that these marks be are bullet strikes from the 1916 fighting. It is unlikely in any case that an entire granite quoin would be replaced, whereas brick might easily be.

The bullet strikes at 25 Northumberland Road are most clearly visible at three locations at the corner of the building. Firstly, there is a bullet strike high up on the southern Haddington Street, side wall, fifth stone from the top, and secondly, there is probable bullet mark on the very same stone, but on the Northumberland Road street frontage side).

Probable bullet strike on granite quoin, fifth from roof, on both this and the Northumberland Road side (Photo: Aidan O’Sullivan).

Thirdly, there is a dramatic bullet strike in the granite quoin on the corner of the front wall just above the level of the porch or hall roof (see below). This latter would appear to be a direct strike from a building directly across the street, possibly shot from a similar height.

Probable bullet strike in the granite quoin at the corner of No. 25 Northumberland Road (Photo: Aidan O’Sullivan)

There are also possible bullet marks around some of the bricks on the Haddington Street side wall, but this remains unconfirmed.

These bullet marks are few enough, probably testifying to Michael Cussen’s repair of his property. They are hardly as dramatic as others we have seen elsewhere around Dublin City, but although faint, they may be echoes of the fierce and bloody battle for No. 25 Northumberland Road that took place a century ago.

But of course, while Northumberland Road had been taken, with grievous casualties amongst the British Sherwood Foresters, the Battle of Mount Street was not yet over…